Dublin cannot be narrated all at once. It is a city that demands chapters, not summaries; it takes you by the hand and urges you to keep wandering even when you think you’ve seen the essentials. That’s why this second post continues the thread of the first: more walks, more discoveries, and that autumnal light that still seems to follow me.

My morning continues at Be Sweet Café, a small, cozy place that catches my attention with its peacock-inspired décor. I step in for a hot chocolate and a vegan pastry: lots of gold, feathers, and whimsy. Sitting there, I feel grateful for all the people who create spaces like this so the rest of us can take a brief refuge from the world.

From there, I head to George Street Arcade, a covered market with a Victorian vibe, where artisan shops, vintage stalls, and tiny cafés coexist as if plucked from another era. Dublin has that timeless charm of the old that never fades.

A few steps away appears Dublin Castle, a curious mix of styles and centuries that has witnessed much of the country’s history. The real gem, however, lies just behind: the Chester Beatty Library, a former library turned museum that houses artistic and religious manuscripts from around the world. It is one of those quiet places that stop time, where the miniatures shine as if freshly painted, and its garden attracts those in search of peace.

Back on the streets, I stumble upon Love Lane, a passage full of colors, tiles, and romantic phrases that seems designed to make you smile for no reason. Nearby, the Temple Bar area bursts with energy: tourists, music, pubs, and the famous The Temple Bar, decorated for Christmas all year round, as if the city refuses to lock away the magic.

The music in Irish pubs like the Temple or the O’Donoghue’s is simply fabulous: no one is immune to it. Once the fiddles, guitars, or voices begin to play, seemingly telling ancient stories, the atmosphere transforms. Musicians interact with the audience as if they were old friends: they laugh, improvise, clap along, and the lyrics—sometimes melancholic, sometimes hilarious—envelop everything.

The fun is genuine, contagious without permission.

I continue wandering among lights, laughter, and songs until I reach The Quays Pub, with its green-and-gold façade, so Irish it could be a postcard. I cross Ha’penny Bridge, delicate and white, one of those bridges that make you pause and look. From there, I photograph the River Liffey, reflecting the city like a moving mirror, and send the picture to my friend Frank, who is Irish: “Are you sure I didn’t get the country wrong?” Judge for yourself by the skies in this photo.

My final bookish stop of the day is The Winding Stair Bookshop, a narrow and charming riverside bookstore, perfect for getting lost among shelves and discovering books that find you before you find them—especially if they have a beautiful cover, like the one I picked up.

From there, I continue to one of the city’s two cathedrals, Christ Church Cathedral, imposing and solemn. A little further awaits St. Patrick’s Cathedral, surrounded by gardens. Both envelop you in that mixture of history and silence only grand cathedrals can offer.

And, as if the city wanted to test my love for it, comes the most Dublin part of the trip: an epic downpour. The kind of rain that doesn’t forgive, accompanying me—shoes soaked—on my visit to Kilmainham Gaol, the former prison turned museum where the weight of Ireland’s recent history is palpable. There, I learned about the Easter Rising and the fate of its leaders. I walked its cold corridors and silent cells and paused before the Virgin painted on one wall by an inmate.

Dublin, even in the rain, remains pure poetry.

Literary Note

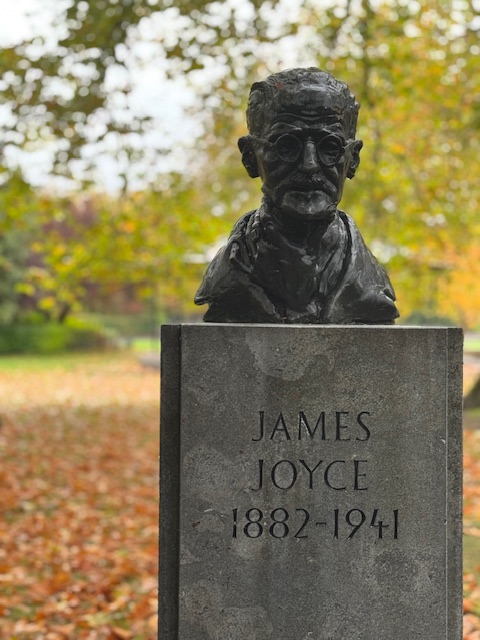

James Joyce is undoubtedly another of Dublin’s most universal writers. His time in 1920s Paris—where Sylvia Beach, the legendary owner of Shakespeare & Co., dared to publish his monumental Ulysses—cemented his literary fame.

But today I want to talk about a different work, one that opened a personal and melancholic window into the everyday life of this city: Dubliners.

Dubliners is a collection of fifteen stories portraying early 20th-century Dublin with sharpness and deep humanity. Joyce captures routines, frustrations, small desires, and silences with moving precision. His stories are like narrow streets you wander slowly, noticing every detail: a conversation at dusk, a party revealing more than it shows, a homecoming under the rain.

As I walk through the city, I feel that many of these scenes still pulse among its buildings, in the lively pubs, in the red brick façades, and in that blend of humor, nostalgia, and warmth so quintessentially Dublin.

That’s why Dubliners accompanies this second part of the journey: understanding Joyce, in a way, is also understanding Dublin.